How to create good one-pagers

A simple way to use documentation as a superpower and improve your communication and decision-making skills.

It is not unusual to see product managers and product teams losing focus on what to build. I’ve seen this happening for many different reasons. Still, perhaps the biggest one is because we treat Product Discovery and Product Delivery as processes instead of conceptual models. The inevitable consequence of this is falling into the famous build trap. Many of us have been there, and probably many still are.

As PMs, we are constantly making discoveries and always working on delivering them to customers. The difference is how much time and effort we balance between each activity and how we approach the aspects of what is indeed discovery and delivery. But there will be another article for that.

This article is about how we can create good one-pagers and use them to our benefit, as I wrote before here, and use them to create an influential experimentation product culture, therefore helping you escape (or not fall into) the build trap.

The premises here are simple:

Most of the time, writing one-pagers starts with the PM

It has to be collaborative—you won’t have all the answers, nor the best ideas

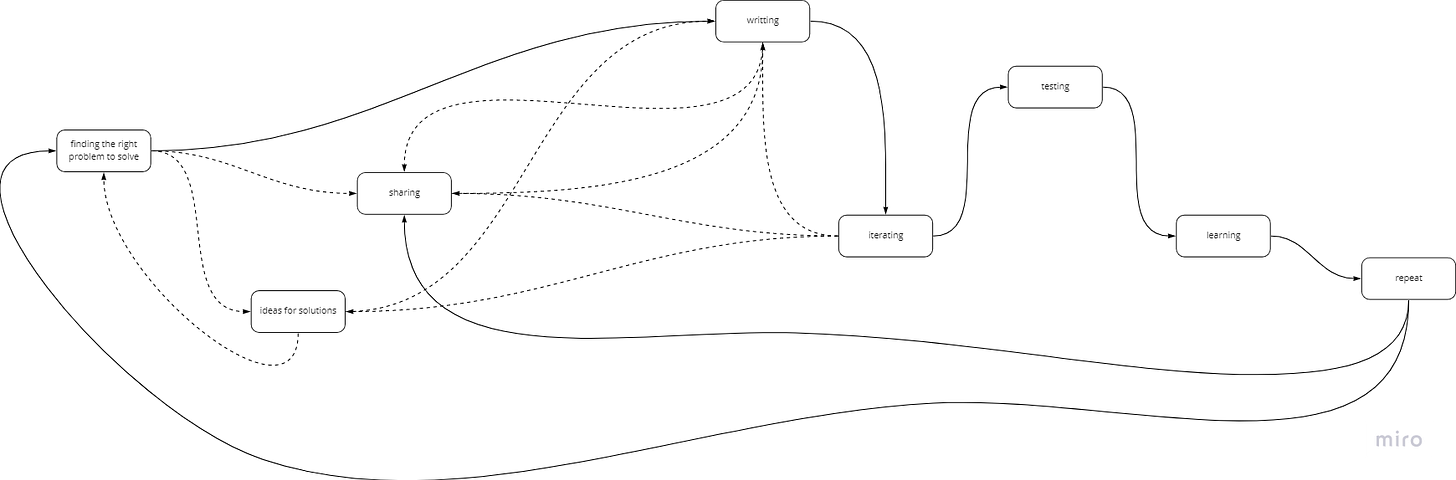

This is not exactly a linear process—and it’s ok.

So, where do we begin? This is my process of creating one-pagers and how I encourage my team to do so.

Finding the right problem to solve

Everything starts by finding (or trying to) the right problem to solve and the right product to build. This is the most challenging thing in our craft and our entire career. Our job is to build the right product and deliver to customers what will solve their problems and generate significant value for our company.

This is not something you do in a week. It takes time, persistence, experimentation, and many, many iterations. What can happen in a week is finding out what makes our core metrics move in the right direction. Nurturing an experimentation culture is demanding but mandatory.

There are many ways to discover good problems to solve and great frameworks to illustrate those problems constructively. The way I usually work and recommend it is to use Teresa Torres’ Opportunity Solution Tree. For those who don’t know this framework, it’s a must-read. It is our responsibility to understand our customers and their journeys deeply. Through that deep knowledge, we find significant problems to solve, or as Teresa frames it, opportunities.

By the way, you are doing this all the time. It shouldn’t start as a project: “let’s find a problem to solve!”. When you are looking at your data, talking to customers, and understanding user behavior on your app, these are all discoveries.

When you realize that, you’ll unlock a lot of mental bandwidth. Use your one-pagers to document potential problems combined with the Opportunity Solution Tree to better visualize how everything is connected.

Remember: the desired outcomes, or north star metric, must drive the experimentation.

Ideas

Good ideas come from everyone and everywhere. There are a couple of tricky things here, though:

The more context and deep knowledge of your customer’s problems you have, the better your focus on the outcome you’ll be. This is important because, although good ideas can come from anyone, it’s your responsibility as a PM to build the right one. Don’t worry. It will not be the first one you make, and you don’t have to get it right out of the gate.

People like to chime in and feel heard, and that’s ok. But remember, it’s your job to decide, and you should know your customer’s problems better than anyone else to make that decision.

Use this document to organize thoughts, filter, and compare them to make better decisions. Ultimately it’s your responsibility to make those decisions. Don’t fall into the trap of deciding by consensus.

The best way of figuring out and deciding which idea to build is to confront your quantitative and qualitative data and answer the question: “how do we test this?”

Everything here is an experiment, a bet. So ensure you have a good answer to that testing question because this will guide everything from here on.

Writing

The process of writing is the most challenging part. You must produce clear, concise, straightforward documents that give the context for somebody else to understand the WHY, WHAT, and HOW you’re pursuing this bet.

Don’t beat yourself up trying to write the perfect document. Writing is a practicable skill, as is any other. The more you practice, the better you’ll be at writing.

Having an excellent template to guide your writing also helps a lot. Whoever is reading your documentation may not have the information you have. Therefore, giving context is paramount.

These one-pagers will serve as a communication tool and an exercise for your writing and thinking processes.

In the beginning, focus on consistency over quality. It’s more important to see things through than to have the perfect document. Make writing your priority. You need time to think, talk to people and write. No good product management is done without this.

Asking for feedback helps a lot.

Sharing

You are not creating this alone and probably won’t conceive the best experiment by yourself either.

Sharing is part of the process because you want your teammates to collaborate and iterate this document with you.

This is not “deciding by consensus.” Instead, this is stakeholder management. So not only you’ll improve your decision-making skills because you’re learning with your team, but you’ll improve your communication skills because you’ll use these documents to communicate your bets.

For me, what guides the sharing timing is threefold:

First, my comfort with the one-pagers coherence is; that it doesn’t have to be complete. It just needs to make sense.

My connection with whom I’m sharing it; this affects point 1 because the better my relationship, the simpler the one-pager may be for this first-time sharing.

The complexity of the problem and the stakeholders’ anxieties with it also affect points 1 and 2.

So, remember these three points to guide you despite not having a golden rule for when you should start sharing your one-pager.

Also, when you’re satisfied with the one-pagers clarity and coherence, share it profusely. Post it on all relevant channels, and tag people you want to comment and stakeholders.

Iterating

It’s cheaper to iterate the document than the product. Use this opportunity to design a good experiment. As this process is collaborative, ask for different points of view from your team and others. Use this moment to create a test to help you find the right path.

Know when to stop. Don’t fall for the scope creep. Instead, remember the most crucial question: “What is the simplest way to test this?”.

Also, remember to set a time frame to finish iterating on the one-pager. Otherwise, you’ll spend as much time as you put on it.

Testing

In designing the experiment, optimize for value. This is what you need to find. Is this bet delivering value for the customer?

Your bets should invariably pursue leading indicators. Be creative in how you test things. Gather real live data from customers. Don’t use high-fidelity prototypes to de-risk value. High-fidelity prototypes test usability, not value.

Differentiate your bets for how long it would take to run them and learn from the results. This will give you a good idea of what you can experiment with in different time frames.

Make sure you and your team put the main flows and key visuals on how to test the hypothesis on the one-pager.

Learn

The focus of this is to learn and build the right product faster. The goal is to shorten your learning cycle. It’s impossible to learn and grow exponentially if it takes 6 months to test or iterate something.

These one-pagers are living documents. Always write new learning and experiment results, and share them with the teams.

We’re not aiming to precisely achieve the desired metric. Instead, we want to test and experiment with ideas to better understand the problem and the direction we’re going. Jim Collins uses the expression “Lead bullets then fire cannonballs,” which is precisely what we are doing here.

A strong experimentation culture aims to lower the risk and uncertainties faster. The success metrics we use in our experiments exist to understand if we are on the right track. If we are finding our way to solving the customer’s problems in a way that creates value for both customers and the company.

Failure is, by definition, the lack of success. But, on the other hand, if success is learning the right path to follow, then our experiments will never fail. At least not in that sense.

If our experiment doesn’t lead us to where we wanted, this is not a failure. Instead, we learned one more path we should not take.

Failures here happen when we’re not able to measure the results correctly. Which leads us to not learn about that specific route.

Innovation is a function of the number of tests you make.

Repeat

You don’t have to work on a single one-pager at a time, but I highly recommend limiting your work to 2 or 3 one-pagers.

This is hard, collaborative, cross-functional work. It takes time and effort to produce good one-pagers and experiment on them.

The structure I use for the one-pagers is super simple and straightforward.

The format matters the least. The important thing is to answer these questions:

What is the objective?

What is the problem? // What is our hypothesis?

How do we test it?

What does success looks like? What metrics to follow? What to expect?

What are our learnings?

Here you can find a template for you to use and share. It’s super simple.

Don’t forget to subscribe and share if you like the content.